Kraigher vs Kraigher - How Tito Escaped Hitler’s “Roesselsprung” Snare

An Original Story

by Wilhelm Kriessmann with Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2012 by Carolyn Yeager

Introduction ….

By the beginning of 1944, Tito’s partisan forces had gained strength in the mountainous regions of Bosnia and parts of Slovenia, Serbia and Croatia of the former Yugoslavia. Churchill himself had come round to support him after discovering his former ally, the royal Cetnik leader General Draza Mihailovich, cooperated with the Croats, Italians and even with the Germans. Close to three Tito divisions were now concentrated in the wild Karst regions of northwest Bosnia; what had been partisan skirmishes in the past now became serious military engagements. From Wolfsschanze headquarters in East Prussia, Col. General Alexander Loehr, Commander in Chief of Heeres Gruppe South East in Belgrade, received orders to eliminate Tito, who had self-promoted himself to Marshall.

One of the most feared German commando leaders, Obersturmbahnfuehrer (Waffen SS Lt. Colonel) Otto Skorzeny sent out three of his most experienced agents – they found Tito’s nest in Drvar, high in the Bosnian mountains. Under top secrecy, Skorzeny gathered special commandos in Croatia, while at the same time the commander of the XV Gebirgsjaegerkorps (mountain troop corps), Col. General Lothar Rendulic (pictured right), like Skorzeny a born Austrian, prepared the operation "Roesselsprung”1 from his headquarters in the Bosnian town of Bihac. Skorzeny stepped aside when one of his agents was caught by Tito partisans ... as part of the operation was now apparently in Tito’s hand.2

The story Kraigher versus Kraigher describes in detail Operation Roesselsprung, staged from different locations in Bosnia, Croatia and Hungary.

*****

He raised his glass, filled to the brim with the fiery slivowitz, high into the smoky air of the karst-cavern and shouted in Serbo-Croatian the birthday salute: “Zivio nasemu Marschalu Tito.” With one big gulp, he emptied the strong plum brandy into his hungry stomach the way all old partisans do. Lt. Colonel George Kraigher had landed only a few hours ago on the secret airstrip Ticevo, but he knew well the customs of his compatriots.

He arrived at the karst-cavern outside Drvar after taking off from General Eaker’s headquarters in Caserta, Italy. Early in May 1944, Tito had moved into his new headquarters in this inhospitable region of West Bosnia. The Lt. Colonel was now sitting across from Tito and his close friends Jovanovic, his Chief of Staff, and Dr. Kardelj, years later to be his Secretary of Foreign Affairs. They were the same vintage: Tito born 1892, Kraigher born 1891, in Postojna, Slovenia, only about 100 km from here, now occupied by German and Italian troops.

Col. Kraigher and his staff colleagues, Lt. Col. Nebeleff and Lt. Crawford, did not visit Tito to congratulate him for his 52nd birthday – though the Serbian bean soup was delicious and the bread from the field bakery was all wheat from the Batschka, they had more important business to tend. Ammunition, first aid kits, radio sets, howitzers, boots and tents were urgently needed by Tito’s partisan army of 250,000 men strong – thirty-seven divisions and twenty-two independent battalions.

They knew that something was cooking around Bihac, Klin, Jajce and Banja Luka – villages and towns close by and further away in the Bosnian Mountains. Battle groups of the 7th SS Mountain division Prinz Eugen and Panzergrenadiere of the 2nd Panzer Army were being assembled. Col. General Lothar Rendulic, Commander in Chief of the 15th Gebirgsjaegerkorps, had just moved his headquarters. Tito’s men didn’t trust the Austrian generals who they said were “mountain foxes and tough like us partisans.” New codes and signals were set up, the drop places cleared and secured. Return flights for the stranded US aircrews that crash landed or parachuted from their damaged aircraft after the disastrous attack at the oilfields in Ploesti were organized – they had to return to their base in Foggia, Italy. Tito’s army was well-run and did not miss much. All three Allies favored him.

Tito with members of the British Mission at his headquarters only days before the attack.

The small town of Drvar, only 1/2 km down the valley from Tito’s cave dwelling, housed Tito’s civil and military administration. A weather station of the US Air Force broadcast daily forecasts to Cairo, and Time Magazine reporter Stoyan Pribichevich wired battle reports to New York. The radio station and the telephone exchange were operating. All three military missions – the British, American and Russian – were accommodated in the nearby villages. The day before, the Yankees and Brits received secret orders to move out of their quarters and set up new offices in the hills behind Tito’s cave.

Tito had finally eliminated his old nemesis Mikhailovich, the Chetnik general loyal to the king. Neither Churchill, who supported Mikhailovich for a long time, nor Roosevelt, and not at all Stalin, delivered to the general his urgently needed supply. Tito was now the one who carried the banner to finish off the German army in the Balkans. Death to the Nemci-Germans, Zivio Tito!

'Juri Kraigher fought with the Serbs in WWII

George Kraigher (the birth book of Postojna still registers his first name as Juri) could not in his wildest dreams imagine that in the first weeks of August 1914 he might have fought against the present Marshal Tito. But indeed it could have happened. Tito, at that time Josip Broz, sergeant in the Habsburg Monarchy’s “kaiserlich koeniglich” (king and kaiser) Regiment 27, was attacking Serbian troops when Juri Kraigher was flying a combat airplane for the Serbian Army.* Already at that time, Serbian chauvinism, bloodlines and home ground were a deeply-rooted matter. It will get still more complicated as this story unfolds. *Correspondant Vinko Avsenak informs me that Juri Kraigher did not fly for the Serbian army as he hoped to do, but actually spent the war as an Italian pow. See Comments below.

After all the logistics were taken care of and the staff officers folded their maps, they spent some time telling stories of long ago. George mentioned how he hated the ruling Habsburgs and their empire as a young student in Postojna. In 1914, he joined King Peter’s Serbian Air Force and then left the kingdom in 1921 at the age of thirty to settle in Texas. He started as a mechanic, became a pilot carrying freight and stunt flying, and ended as chief pilot and operations manager of Pan American Airlines. He met and befriended Charles Lindbergh in 1929. When WWII broke out, PAA sent him to Africa, traveling between Dakar and Casablanca, in search of the proper place for transatlantic routes. When Roosevelt entered the war to help out Churchill, George Kraigher joined the staff of General Ira Eaker, US Army Air Corps-Mediterranean Region, first at Algiers and a few months later in Caserta’s royal palace.

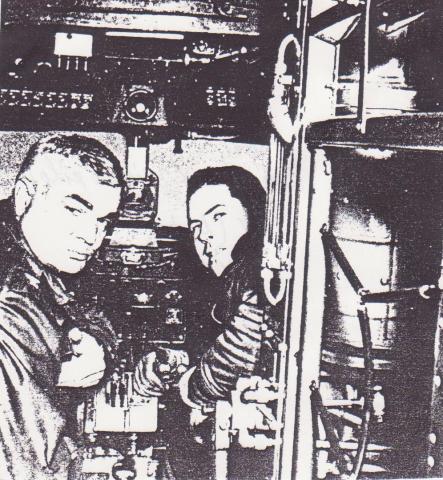

George Kraigher (far left) pilot of a DC 4 ferrying and picking up parachuted bomber crews at the airstrip near Drvar.

So far, Col. Kraigher had flown 45 missions with the B25 and C47, dropping supply over marked places in the Bosnian Mountains and even landing on a small field strip. He was known for his daring flights into Tito’s land and beyond. Hundreds of stranded US pilot’s returned to their bases in Italy thanks to Kraigher’s adventurous rescue flights.

"Juri" Kraigher, left, in the cockpit of a DC 4 getting ready for one of many supply flights from Brindisi, Italy to airstrips in Tito`s controlled region.

__________________

Tito listened, but did not talk; he couldn’t reveal his military past. His regiment, the k&k 27th, attacked Serbian troops in August 1914. Zugfuehrer (Sergeant) Josip Broz, later Marshal Tito, surely earned his three stars. He scooped his regiment’s fencing champion title. He was a competent leader and liked by common soldiers and officers. He spoke an Austrian-coloured German with a Slovenian intonation, being born at the Slovenian-Croatian border – all Habsburg territory. His father was Croat, his mother Slovenian. From the Serbian war scene, his regiment was then transferred to the Galician front. Tito was wounded; the larger part of the regiment – mostly Slovenians and Croatians – had run over to the Russian side and ended in a POW camp in Russia. Tito recovered in a Russian hospital and, as a Russian confidant, ran an Austrian POW camp in Siberia. Adventurous and mysterious was his way to the Yugoslavian partisans. As a deputy of the Comintern (the International branch of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union), he laid the base for Yugoslavia’s underground Communist Party. The kingdom’s secret police chased him, but he found shelter several times close by in Austria. When the Serbian Air Force generals toppled the Axis-friendly government of Prince Paul in 1941, Tito was ready.

It was close to midnight when they shook hands with partisan fervor in their eyes. Tito, Jovanovich and Kardelj retired to the sleeping quarters of the cave; the waterfall at the end of the grotto had dried out some time ago so the soothing effect of running water was missing. Colonel Kraigher, Lt. Col. Nebeleff and Lt. Crawford hurried to their new quarters outside the village; Kraigher wanted to leave with his driver very early next morning to reach the strip at Ticevo and take off for Caserta.

______________________

At their headquarters in Bihac, Col. General Lothar Rendulic, Commander in Chief of XV Gebirgscorps; Waffen SS General Otto Kumm, 7th SS Gebirgsdivision Prinz Eugen; First Lt. Kurt Rybka, Commander of the SS Parachute Battalion 500; and Capt. Batrup, First Parachute division, were bent over the large scaled maps and aerial photographs taken by an Arado reconnaissance airplane a few days ago. They closely studied Drvar and its immediate neighborhood while the rest of the headquarters hummed with activity. Two days previous, Rendulic’s staff had received Hitler’s go-ahead from Wolfsschanze for the Roesselsprung operation. On May 25th at 5:00 in the morning, one of the most daring operations of WWII would begin. Parachutists, glider troops and ground infantry were concentrated in the region of Petrovac Gavar in the mountains of West Bosnia, to catch Tito and his staff in Drvar.

Franz Kraigher was a veteran of the Abwehrkampf, 1919-20

In early April 1944, Hauptmann Franz Kraigher, member of the Abwehr (Army Intelligence) SE at Wilhelm Canaris’headquarters in Berlin, delivered the alarming report that Tito had moved his headquarters to the mountains of West Bosnia – Jajce was empty. But Kraigher’s excellent connections to Mikhailovich, the King’s Chetnik general and Tito's archenemy, paid off. Mikhailovich received the news of Tito’s new hiding place from some British liaison officers attached to Tito’s headquarters, but still loyal to their old ally. Mikhailovich’s agents passed the word on to Kraigher. All through the spring of 1944, the connection between Mikhailovich and the Abwehr functioned smoothly. From the Tirpitz-Ufer, the Abwehr headquarters in Berlin, the wires ran hot to Col. Gen. Alexander Loehr’s Southeast headquarters in Belgrade where Kraigher was stationed, and to their German embassy in Agram.

Left, Captain Franz Kraigher in Berlin, 1943 and below, in 1960 a civilian again back home in Feistritz im Rosental.

Austrians (or Ostmaerkers) occupied the key positions: Loehr, candidate of the traditional Military Academy of Wiener Neustadt and former Commander of the Austrian Air Force; Hermann Neubacher, former mayor of Vienna, now special Balkan envoy; General Glaise-Horstenau, former king & kaiser officer and an old Balkan hand. Also two captains, Kraigher and Matt, and special agents Staerker and Ott. A few weeks earlier they were joined by Otto Skorzeny, once a wild member of a Viennese student corps, now chief of all special operations with the rank of Lt. Col. in the Waffen SS, receiving his orders directly from the OKW. Skorzeny got Kraigher’s reports in addition to those of his own agents, and messages from the “Brandenburger” special operations units. All that spreading around of information made him nervous and suspicious, and he nearly called the operation off. Not quite, though, because he knew the core of the commando enterprise – the parachute drop of the SS Fallschirmjaeger Battalion 500 – was wrapped in deep secrecy. He gave them the green light.

Franz Kraigher was born in 1893 in Feistritz im Rosental, Kaernten, the southernmost part of Austria. He earned his first laurels during the Kaerntner "Abwehrkampf” of 1919-1920, fighting against the intrusion of Yugoslavian troops. He helped Dr. Steinacher organize the first resistance and the preparations for the plebiscite of October 1920, and was responsible that local resistance in the two Southern valleys against the terror of the invaders was alive and strong. Thanks to the activities of these two men, and numerous others, the intruders were forced to leave; Kaernten remained united.

Kraigher had fought in WWI as a First Lieutenant, then worked for years as a CPA at the local factory and was called back to military service when WWII began. He joined Canaris’ Abwehr in Berlin, SE department, in 1941. Promoted to a Captain, he later moved to Belgrade and to the inner circle of the Balkan experts at Loehr’s headquarters. From his agent, he received detailed information on the position of Tito’s Proletarian Division outside Drvar, the cadet academy, the weather and radio station of the Americans, and the battle-readiness of the Proletarian Brigade at the upper part of the Unac rivulet. Tito’s new cavern accommodations were also revealed. What Kraigher did not know was that his agent had been captured by Tito’s underground and, under severe torture, had admitted to having relayed all that information to the Germans. Thus the partisan staff knew well in advance what Rendulic and the Prinz Eugen had up their sleeves. They would be ready.

They expected the movement of the attack units to come from Klin in the West, Bihac from the North and Jalce & Kluj from the Southeast; out of the sky the Ju 87 Stukas and ME 110 fighters would dive down. Drvar was evacuated, the surrounding hills fortified, and earth bunkers reinforced. Jovanovic, Tito’s Chief of Staff, had not the faintest idea, however, what was brewing in the sky above Drvar – the existence and task of the SS Parachute Batallion 500.

The Attack

Kurt Rybka, the young SS First Lieutenant, commander of the Parachute Battalion, assembled his troops – soldiers of the mysterious Brandenburg division, members of the Abwehr, parachutists and pilots of the Luftwaffe, and Bosnian volunteers. Top secrecy ruled when the following units gathered between May 22 and 24.3

A) At the Agram (Zagreb) airport:

GroupPanther

110 men of the Brandenburg special units Benesch and Savadil, a Bosnian special unit, and pilots and liaison officers of the Luftwaffe, split into five sub-groups.

GroupGreifen

40 men to capture the British mission

Group Stuermer

50 men to capture the Russian mission.

GroupBrechen

50 men to capture the U.S. mission.

Group Draufgaenger

50 men (Avadil, plus the Bosnian unit) to destroy the radio and telephone station in Drvar and collect intelligence material.

Total strength: 300 men occupying 23 DFS (Deutsche Forschungs Anstalt) gliders, which won glory at the Belgian fortress Eben Emael at the beginning of the West offensive, 1940. The well-proven Henschel 124 pulled them on ropes. Take off at 6:10 a.m. … over target 7:00 a.m. … landing at the target after the parachutists jump and secure the landing area.

B) At Nagy Betschkerek (Hungary) airport:

314 men – SS parachute battalion 500 pilots and jump-masters from the Luftwaffe, transported by six Ju 52 aircraft, also of past glory in Holland, Norway and Crete. First wave at 7:00 a.m. with a 20 second parachute glide.

C) At Banja Luka (Bosnia) airport:

220 men – SS parachute battalion 500 and Lehrschool parachute battalion as the second wave to be picked up by the Ju 52’s returning from Drvar, depending on the battle situation. At the target between 8:00 and 9:00 a.m.; called in by radio message.

From his headquarters in Bihac, Col. General Rendulic radioed his code message “Marsch” to all units at 5:00 a.m., May 25 – the columns of Gebirgsjaeger SS Prinz Eugen, the Panzergrenadiere of 2nd Panzer, and the battlegroup Williams of the 373 Grenadier Division move out of their position around Drvar. Williams should arrive first at Drvar and relieve SS Parachute Battalion 500.

Thundering explosions jolted Tito, Kardelj, Jovanovic and Kraigher awake. Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers and Messerschmidt 109 and 110 fighters raced over the hills and the roofs of the town, spitting fire and lead, bombs and grenades over all. Only a few machine guns responded. There were no anti-aircraft guns, no Allied aircraft around; the Luftwaffe controlled the sky above Drvar.

Ju 52s dropping paratroopers

Ju 52s dropping paratroopers

Tito and Kardelj jumped out of their cave onto the wood-balcony, looking down to the village about 5 km distant from their grotto. Stukas and Messerschmidts were disappearing behind the hills and treetops when all of a sudden six Ju 52 three-engine aircraft appeared low in the sky. White parachutes opened everywhere and right behind them the gliders sailed down like hawks diving towards their targets.

Group Panther landed with six of their gliders right in front of Tito’s grotto. The first crashed and tumbled head over – no survivors. Tito’s guard, a company of about 350 men and women, immediately began shooting. Forward, the way led to certain death. The bushy slopes below the cave were crowded with parachutists and from the flank a German MG 42 pounded in a high staccato against the grotto’s rocks.

“Get out of the cave! Take the rope and up through the high open shaft. There is no waterfall obstructing our way out; it’s all dry!” And they climbed and ran and reached the top of the hill which was kept secure and open by the hard-fighting of the 1st Proletarian Brigade under Koca Popovic. Tito and Kardelj, with part of their staff, did finally reach the field rail station Potoci and arrived safely within the partisan-controlled area of that mountainous Bosnian region. Col Kraigher was one of them. Lt. Col Nebeleff got lost and wandered through the forest until he reached the coast. Lt. Crawford was killed by MG fire. Kraigher then got separated from Tito and his staff; he reached Ticevo and took off with a small aircraft for Caserta, reporting to his friend and commander Lt. General Eaker. The general reacted immediately and discharged 500 aircraft (300 bombers and 200 fighters) to help the troubled partisans. The air raid came too late to save Drvar, but was strong enough to cause heavy losses amongst the Germans for the next 10 days.

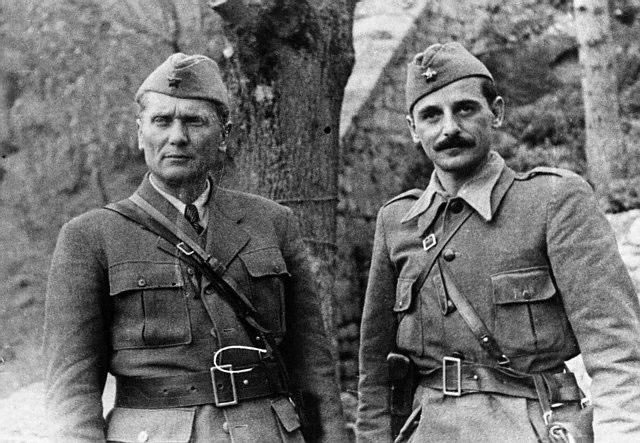

Tito with Kocha Popovitch in 1943

Tito with Kocha Popovitch in 1943

Although Tito avoided capture, he suffered substantial loss, including his extensive communications system and other valuable booty. He wanted to stay and fight with his comrades, but his staff forced him to leave. He watched his ordinance officer get shot through the head. Knowing about the five German battle groups closing in on Drvar, he ordered his own people to retreat, but they would hear nothing of it; they wished to crush the SS paras.

[On July 3, Tito took off with a DC 3 (US Dakota aircraft) from the airfield in Kupres, southeast of Jaice, and landed in Bari, Italy. The British liaison officer accompanying Tito nearly lost his pants when pilot and co-pilot greeted him with a grinning “zdrastwutje” (Russian ‘hello’). Soviets, not Brits or Yankees, flew Tito to freedom! Stalin triumphed. General Eaker and Col. Kraigher did not like it.] __________________________

Another view of parachute drop with glider in the foreground.

Another view of parachute drop with glider in the foreground.

The jump of the parachutists functioned flawlessly. Dvar’s exits were barricaded, landing spots for the gliders secured. One after another hit the hard soil, rolled out, crashed against bushes and trees, and dispatched soldiers and heavy arms. Group Draufgaenger stormed the radio station and telephone center, fighting at close range with no mercy given and heavy losses. Dark smoke floated all around. The lead glider of Group Greifen missed the landing area and crashed against the bank of the river Unac, making it a total loss. Their target, the British Military Mission, was not located there anymore; it had moved two days previous, together with the Americans and Russians, behind Tito’s grotto.

Following his secret order, SS Commander Rybka landed with his glider group ‘Panther’ right at the entrance of Drvar. Around him were the remaining glider planes. Next to a broken glider, he set up his command post. He could see the grotto’s dark entrance from this spot, could hear the battle noise and the bloody resistance of the defenders. Shortly after 8:00 a.m. he recognized that the first storming of the cave had failed. Red flares shot into the morning sky as a signal for regrouping and concentration. The 100 men of Groups Stuermer and Brechen were pulled back as reserve units – their target no longer existed, the houses were empty.

Through the thick, bushy slope and over stony ground, the attack moved uphill. Heavy fusillades of MG and howitzer fire hit into the paras and from their left flank young partisans from the cadet school in nearby Sipouyani stormed. Again, a man-to-man fight with pistol and hand grenades began. Rybka wanted Stuka attacks, but his own men were in the thick.

At 8:30 the second wave of parachutists from Banja Luka jumped right into heavy gunfire, suffering losses, but managed to reach Rybka’s command post. Reinforced, he decided to attack the grotto again, but ran into fierce defense by the 1st Partisan Brigade and was seriously wounded. The battalion was close to being cut off. They retreated behind the wall of the cemetery, dead tired, hungry, without water, and prepared for an all-round defense. Glaring rockets lit up the dark sky at short intervals; they knew the partisans would attack. Holding on, they repelled a break-in and three bloody attacks before the first advance of Group Williams broke through at early dawn; hours later, the units from Bihac and Kluj also arrived. The partisans withdrew from Drvar and the whole region came under German control. The badly wounded Rybka was flown out by the Fieseler Storch aircraft that was to have taken the captured Tito to Rendulic in Bihac.

The Aftermath

Hitler headquarters at Rastenburg/Wolfsschanze was nervous. No reports had yet reached Rendulic or Loehr; the radio station in Drvar had gone up in fire and smoke. Only when the battle group Williams reached the chaotic battlefield did the message go out that Tito had escaped. They found his Marshal’s uniform, his boots and also his jeep. Upon receiving the message from Rendulic, General Keitel said, “I do not dare approach the Fuehrer with that report.” And, indeed, Hitler was furious and retorted with acid irony: “We could have gotten that uniform more cheaply by tailoring it ourselves! Send it to Vienna – that’s where Rendulic comes from.” (Rendulic hailed from Styria.) Weeks later, the Viennese could eye Tito’s green and gold-rimmed Marshal’s jacket and the wide Russian styled trousers at a display at the Army Museum.

The XV Gebirgskorps reported to Col. Gen Loehr: Operation Roesselsprung total losses: 213 dead, 881 wounded, 57 missing.4 The official daily “Wehrmachtsbericht” (Armed Forces Report) June 6, said: “Troops of the Army and Waffen SS, Col.General Rendulic, Commander in Chief, attacked and destroyed, supported by bombers and battle cruisers of the Luftwaffe, the center of Tito’s partisan groups in Croatia. The enemy lost 6240 men, numerous weapons and supply were captured. The 7th SS Mountain Division Prinz Eugen, General Kumm, and the SS Parachute Battalion 500, 1st Lt. Rybka, have proven themselves excellently.”

Marshal Tito, meanwhile, cruised on board a British destroyer from Brindisi to the island of Vis and established his new headquarters there – well-fortified and well-staffed. Rendulic and Skorzeny contemplated an operation on Vis, however, a few weeks later Skorzeny liberated Mussolini on top of the Gran Sasso with the same DFS Glider 320 used in Drvar. Col. General Rendulic took over the army in Kurland.

In early October, Tito marched into Belgrade and turned the former kingdom into the People’s Republic. During the following decades, he played, together with Nehru, Nasser and Sukarno, an important role in world politics as The Third Power. Tito kept his Yugoslavia tightly together, regardless of its strong ethnic divergences, and showed independence and backbone against Stalin’s bullying. At his zenith, he enjoyed a lifestyle similar to Reichsmarschall Goering – glamorous uniforms, luxury yachts on the Adriatic, splendid parties at his various villas and a jovial host at hunting parties in the former “partisan” forests. After his death, the People’s Republic disintegrated, but Tito is still adulated in most of the new states as the heroic partisan marshal, and founder of the Republic of Yugoslavia.

Not as glamorous was the life ending of Tito’s adversaries. Alexander Loehr, Col. General and last Commander of the German forces in the Balkan war scene, left his headquarters in Styria, Austria in early May 1945, against the advice of his staff, to negotiate an armistice and the safe return of his troops, trusting the assurance of safe conduct by the partisan general. After they had put down their weapons, they were told they would be allowed cross the border into Austria. Loehr never returned and was shamefully put under the gallows. His soldiers, well over ten thousand, laid their armor down and hoped to cross the Austrian border. Instead, they were marched south, starved to death, murdered and dumped into karst caves in Southern Slovenia.

Col. Rendulic was called back from the Kurland front to lead Army South-Slovakia/Hungary in April 1945. He spent three years as a prisoner of war, after which, in 1948, he was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment as a war criminal, released in 1951. He died in Graz, Austria in 1971. SS Captain Rybka recuperated slowly from his serious wound, joining Skorzeny’s staff in May 1945. His tracks were lost around Bad Aussee and Radstadt, Austria.

The two Kraighers naturally went quite different ways. Colonel George Kraigher remained until the end of the war at Gen. Eaker’s staff in Caserta. Eaker led the US Air Force at the invasion of Southern France. Kraigher returned back home, flew for a short while as first captain for Pan American Airways, then for years managing PAA’s flight operations. Flying, horses, and dogs were his favorites and he enjoyed them as a bachelor living in Litchfield, Connecticut. On his many trips, he always searched for Kraighers, and found several of them. Pamela and her family in New Douglas, Illinois … Eberhard the former city planner of Klagenfurt … Nadja Kraigher in Ljublana. George Kraigher, with the rank of Major General, passed away in 1984 at the ripe age of ninety-three.

After Roesselsprung, Captain Franz Kraigher remained for awhile at the headquarters in Belgrade, then moved to Agram/Zagreb as the Soviets approached. There he was told about the tragic end of Mikhailovich, the king’s confidant-Chetnik General: Caught by Tito’s agents hiding in a foxhole in Macedonia and accused as a traitor to his country, he was shot in early 1945.

Franz Kraigher then moved from Agram to Austria’s Western Province Vorarlberg, where he was for months interviewed by the Bureaux Deuxieme in Austria’s French-occupied zone. In 1948, he was allowed to return to his family in Feistritz, Kaernten, and worked again as a CPA at the battery factory, Jungfer. At the cemetery in nearby Suetschach, he rests at the Kraigher family gravesite – far away from the other Kraigher monument in Litchfield, Connecticut, thus ending the Kraigher versus Kraigher saga.

Endnotes

-

Roesselsprung means “young horse’s jump”

-

Otto Skorzeny, Meine Kommando Unternehmen, 1993, Universitas Verlag Muenchen, pp. 201-02.

-

Otto Kumm, Prinz Eugen:The History of the 7 SS Mountain Division “Prinz Eugen”, J.J.Fedorowicz Publishing, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 1995, pp. 118-19.

-

Kumm, pp.126-7.